Summary:

Certain films evoke a sense of "manufactured nostalgia," creating emotional connections that feel like memories of experiences never lived. This phenomenon arises from a combination of visual styles, sound design, and storytelling that tap into universal feelings of longing and identity. Directors like Wes Anderson and Sofia Coppola excel in crafting these cinematic worlds, where nostalgia isn't tied to historical accuracy but to emotional resonance, allowing viewers to explore the gap between past and present selves.

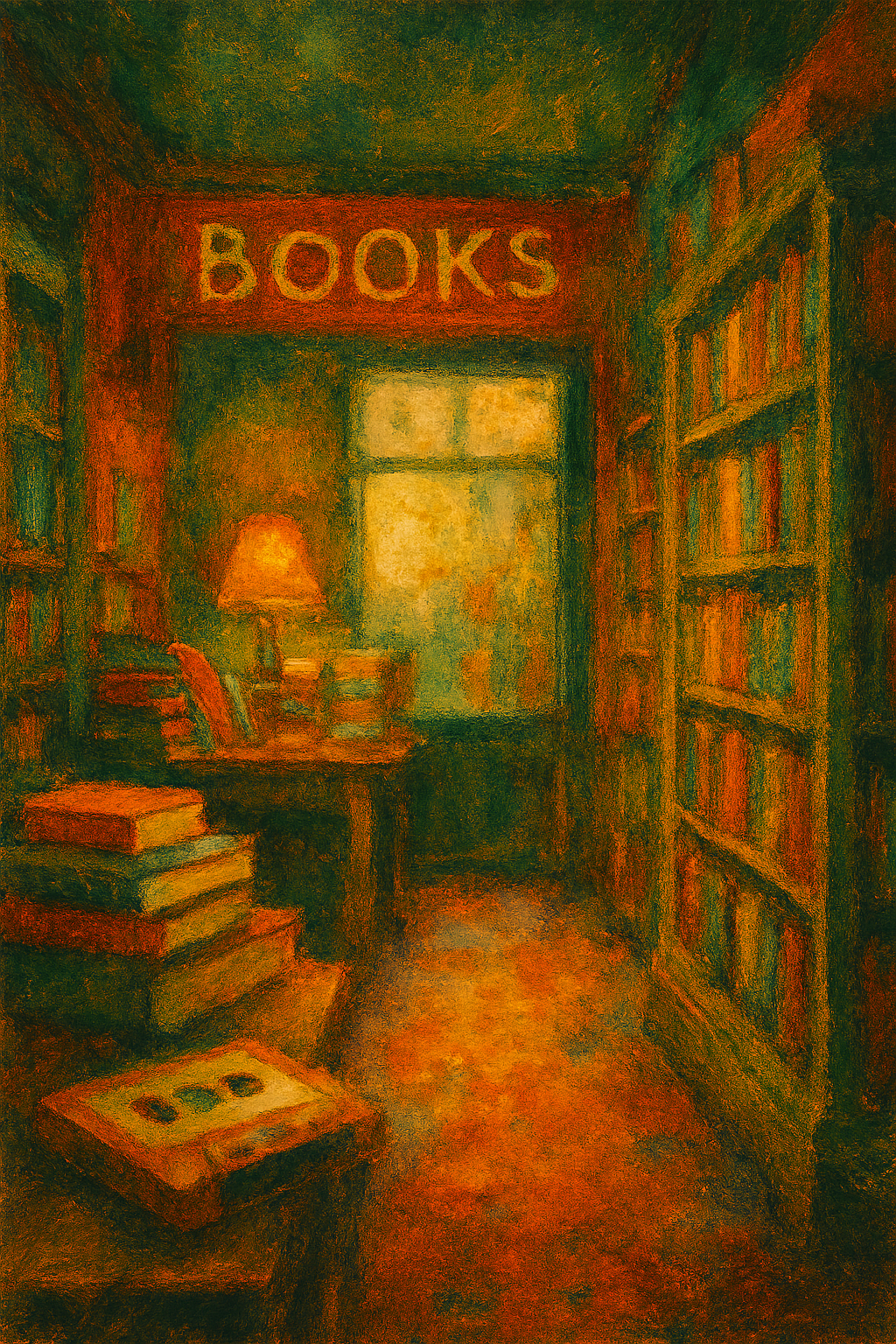

Memory plays tricks on us, especially when it comes to films. Sometimes you'll watch a movie for the very first time and feel an overwhelming sense of having lived through it before—not the plot, but the feeling itself. It's like discovering a photograph of a summer you never experienced, yet somehow the warmth of that sun still touches your skin. This peculiar phenomenon happens when certain films tap into a collective emotional reservoir, creating what I call "manufactured nostalgia"—that bittersweet ache for times and places that exist only in the amber glow of celluloid dreams.

Some films don’t tell stories — they unlock memories you never lived.

This peculiar phenomenon happens when certain films tap into a collective emotional reservoir, creating what I call “manufactured nostalgia”—that bittersweet ache for times and places that exist only in the amber glow of celluloid dreams. It’s the same emotional territory explored in movies that make you feel something, where cinema becomes a mirror for feelings, we can’t quite articulate.

I've spent years trying to understand why some movies feel like memories rather than stories. It started during a late-night screening of The Royal Tenenbaums in college. I'd never seen it before, yet watching those characters move through their faded brownstone felt like revisiting my own childhood home—which was nothing like a brownstone and nowhere near New York. The film had somehow bottled a feeling I recognized but couldn't name.

The Architecture of Remembered Feelings

Films that evoke nostalgia share certain DNA markers, though they manifest differently across genres and decades. Color grading plays a massive role—those warm, slightly oversaturated hues that make everything look like it was shot through honey.

Think about how Amélie bathes Paris in greens and reds that shouldn't exist in nature but somehow capture exactly how the city feels in your imagination. Or consider the sun-bleached palette of Stand by Me, where even the dirt roads seem to glow with significance. These visual signatures echo the emotional palettes explored in movies that feel like autumn, where mood becomes the story.

Nostalgia isn’t about the past — it’s about who we were becoming.

But it goes deeper than visual tricks. These movies understand that nostalgia isn't really about the past—it's about the gap between who we were and who we've become. They create spaces where that gap feels navigable, even beautiful. This is the same emotional terrain that drives so many morally gray protagonists, characters who live in the tension between identity, memory, and transformation.

Sound design matters enormously here. The crackle of a vinyl record in Lost in Translation, the distant lawnmowers in The Virgin Suicides, the muffled underwater sounds in The Graduate—these aren’t just atmospheric choices. They’re emotional cues that bypass our conscious minds and speak directly to something primal about how we process memory.

When Wes Anderson Invented His Own Past

Nobody manufactures nostalgia quite like Wes Anderson. His films don’t reference real history so much as they create alternate timelines where the past looks exactly how we wish it did. The Grand Budapest Hotel takes place in a Europe that never existed, during a war that’s both all wars and no war.

Anderson’s trick is understanding that nostalgia is fundamentally about loss. Every perfectly symmetrical shot carries the weight of its own eventual destruction. The hotel will decline, the family will scatter, the moment will pass. We're watching memories being formed and lost simultaneously.

Wes Anderson films feel like memories of a world that never existed — and that’s the point.

Moonrise Kingdom might be his masterpiece in this regard. Set in 1965 on a fictional New England island, it captures the feeling of being twelve years old better than any documentary could. Not the facts of being twelve—the feeling.

The Goonies Never Say Die (But We All Grew Up)

The Goonies has become patient zero for a particular strain of nostalgic cinema. But here’s the twist: it feels nostalgic even to people who weren’t alive in the ’80s. My nephew, born in 2010, watches it with the same wistful look I had when I first saw it in the ’90s. This points to something crucial about nostalgic films—they're not really about when they were made or when they're set. They're about a feeling of possibility that we associate with youth, regardless of when our youth actually happened.

The Goonies remembers what it felt like to believe adventure was waiting just beyond the edge of town.

The film treats its child characters with rare respect. They’re not miniature adults or comic relief; they’re fully realized people dealing with real problems—foreclosure, divorce, feeling like a freak—through the lens of a treasure hunt.

Sofia Coppola and the Art of Beautiful Emptiness

If Anderson creates nostalgia through maximalism, Sofia Coppola achieves it through absence. Her films feel like memories because they focus on the spaces between events—the quiet, transitional moments that paradoxically linger longest. Lost in Translation is a meditation on disconnection. The Virgin Suicides is nostalgia filtered through adolescent longing and adult regret. Coppola doesn’t just depict the past — she depicts how we remember it.

Coppola films feel like remembering a dream you never fully woke up from.

The Eternal Summer of Coming-of-Age Cinema

Coming-of-age films and nostalgia are almost synonymous. Growing up is inherently nostalgic — you’re constantly leaving behind versions of yourself.

Stand by Me remains the gold standard. Its entire emotional architecture is built on preemptive loss. Call Me By Your Name achieves something similar through sensual specificity and emotional clarity.

The best coming-of-age films make you mourn a childhood you never had.

When the ’80s Became a Feeling

Films like Stranger Things, Super 8, and It don’t portray the 1980s — they portray the idea of the 1980s. It’s nostalgia filtered through nostalgia.

Super 8 is nostalgia squared: a 2011 film set in 1979 that feels like it was made in 1985.

The French New Wave of Memory

The French were making films that feel like memories long before American directors caught on. The 400 Blows, Jules and Jim, Breathless — these films invented the emotional grammar of cinematic nostalgia.

And then there’s Amélie, the international blueprint for whimsical nostalgia. Jeunet’s Paris exists outside of time — a city remembered rather than lived.

Amélie doesn’t just evoke nostalgia — it weaponizes it.

The Terrence Malick Problem

Malick’s films feel less like narratives and more like recovered memories. The Tree of Life attempts to capture the sensation of remembering your entire childhood in a single breath.

His films are fragmentary, sensory, emotional — which is why they can feel both profound and frustrating.

Digital Nostalgia and the Death of Film Grain

The shift from film to digital changed how movies create nostalgia. Film grain itself became nostalgic — a texture we now add artificially to evoke a feeling. We’re nostalgic for the way movies used to look, so we make new movies look old, which makes us nostalgic for when old-looking movies were actually old.

The Soundtrack of Memory

Music is one of the most powerful engines of nostalgia. A single song can transport you across decades of emotional history. Sometimes it’s needle drops. Sometimes it’s original scores that feel like memories you’ve always had but never heard.

Music is the emotional time machine of cinema.

Why We Crave the Ache

Nostalgia is a safe way to experience loss. It lets us practice grieving for things that never really existed. Nostalgic films remind us that the present will someday be the past — that this moment might be the good old days.

The Future of the Past

We’re already nostalgic for the 2000s. Films like Lady Bird and Eighth Grade treat the recent past with the same golden glow once reserved for the 1950s. Maybe that’s the truth about nostalgic cinema: it’s not about the past at all. It’s about the human need to make meaning from memory.

We’re all trying to find our way back to a home that might have only existed in the movies.

FAQ: Movies That Feel Like Nostalgia

Why do some movies feel nostalgic even if I’ve never seen them before?

Because nostalgia isn’t about memory — it’s about emotional recognition. Films tap into universal sensory cues, moods, and emotional rhythms that feel familiar even without personal history.

Do nostalgic films have to be set in the past?

No. Many nostalgic films create a sense of emotional pastness through color, sound, pacing, and tone rather than historical setting.

Why do coming-of-age films feel especially nostalgic?

Because growing up is inherently nostalgic — you’re constantly leaving behind versions of yourself.

What makes the 1980s such a nostalgic decade in cinema?

The ’80s became a cultural shorthand for adventure, innocence, and analog warmth. Modern films recreate the *idea* of the ’80s rather than the reality.

Why do directors like Wes Anderson and Sofia Coppola evoke nostalgia so effectively?

They use visual and emotional stylization — symmetry, color palettes, silence, longing — to create worlds that feel like memories rather than stories.

Quiz: How Nostalgic Is Your Movie Taste?

- Which film aesthetic hits you hardest?

A) Warm film grain

B) Dreamy soft focus

C) Sun‑bleached summer palettes

D) Analog ’80s adventure vibes - Which scene feels most like a memory?

A) The pool in The Graduate

B) The hallway in Lost in Translation

C) The camp scenes in Moonrise Kingdom

D) The train tracks in Stand by Me - What kind of nostalgia hits you hardest?

A) Childhood friendships

B) First love

C) Summers that felt endless

D) Places you’ve never been but somehow remember - Which director’s emotional world feels most like your own?

A) Wes Anderson

B) Sofia Coppola

C) Luca Guadagnino

D) J.J. Abrams (early era) - Your nostalgia score:

Mostly A — Aesthetic Nostalgist

Mostly B — Emotional Nostalgist

Mostly C — Sensory Nostalgist

Mostly D — Adventure Nostalgist

Video Spotlight: The Cinematic Language of Nostalgia

This scene from Stand by Me captures the emotional architecture of nostalgia — innocence, danger, friendship, and the ache of growing up.

Further Reading

- Svetlana Boym — The Future of Nostalgia

- Vera Dika — Recycled Culture in Contemporary Art and Film

- Fredric Jameson — Postmodernism

- Christine Sprengler — Screening Nostalgia

Grow through the stories that shape you!

If you’re exploring the back story of movies why not binge on these cinematic shorts! Plot twists that you never see coming, the “why” in what a story is teaching you, and the art of being seen then join me on YouTube! I create thoughtful, cinematic lessons designed to help you see your life with more compassion, courage, and intention.

Subscribe to Back Story Movies on YouTube! →Did I forget to mention, get more creativity in your life and shop the merch at Creativity Is Expression! Visit now @